History of Owlpen and its owners

OWLPEN (pronounced locally “Ole-pen”) derives its name, it is thought, from the Saxon thegn, Olla, who first set up his ‘pen‘, or enclosure, by the springs that rise under the foundations, in the ninth century.

The immediate area has many signs of earlier settlement. There are sites of round barrows and standing stones within a short walk of the manor. Uley Bury — the long, bare, flat-topped hill which shields the manor from the west wind — is an impressive multi-vallate, scarp-edge hill-fort of the middle iron age (say, 300 B.C.), commanding spectacular views over the Severn Vale. Just by it is Hetty Pegler’s Tump, one of the best preserved middle neolithic chambered long barrows of the Cotswold-Severn group (2,900-2,400 B.C.).

On the hill between the manor and Uley Bury is the West Hill Romano-Celtic temple site from the early fourth century A.D.. This religious complex yielded the head of its titular god of Mercury, “one of the most important Roman sculptures to be found in Britain” (The Times), which is now in the British Museum. Other finds, including numerous lead curses, attest the continuing importance of the area as a centre for ritual and worship for over five thousand years.

The nucleus of the manor is believed to be on an early medieval site, probably linked to nine others in the Upper Thames basin where churches dedicated to the Holy Cross were set up in an era of Celtic missionary activity at the turn of the sixth century.

The Owlpen estate has a recorded history of close on a thousand years, well documented for a manor of its size, whose owners were squires residing, far from typically in the earlier medieval period, on their own manor. Despite many reversals, they were never alienated from it; nor was it bought or sold before the twentieth century. Its history connects it with a number of old families, houses and estates throughout south west England, as well as Ireland, and with talented artists and writers and famous visitors.

de Olepenne family (1100-1462)

By 1174, the de Olepenne family had already been settled there for two generations, no doubt calling themselves after the place. We have records of at least ten successive generations of them holding uninterrupted possession as lords of the manor of Owlpen. They became local landowners of some importance, acquiring land holdings in neighbouring parishes from Tetbury to Cam and Coaley, and occur as suitors and litigants, as benefactors to the local abbeys and hospitals.

The de Olepennes were always faithful henchmen to their feudal overlords, the Berkeleys of Berkeley Castle, whose charters they regularly attested, whose wills they administered as executors (as in 1281), and with whom they served on crusades and military campaigns in France and Spain.

The de Olepennes were pious ecclesiastical benefactors. In the twelfth century, the father of Bartholomew “de Holepenna” died clothed in the habit of the Benedictine monks of St Peter’s Abbey, Gloucester; Bartholomew confirmed his father’s gift of a hide of land to the Abbey in 1174 (with his son Simon’s consent) and was a benefactor also to St Bartholomew’s Hospital, Gloucester; in 1227, a James de Olepenne was attorney to the abbots of Cirencester; John de Olepenne was a benefactor to St Bartholomew’s Hospital again in 1325.

In 1329 John de Olepenne III was made a ward, in his “nonage”, or minority, of the local landowner, Walter de Cheltenham. In 1350 he was threatened with being “distrayned in his lands”, but let off “because he continued many years beyond the seas with Maurice de Berkeley”, probably accompanying his overlord in Aquitaine and on the French Crécy-Calais campaigns of 1346-7. He lengthened the vowel of his name to Owlepenne, from which the corruption ‘Owlpen‘ (or ‘Wolpen‘) developed in the next century.

Robert Owlepenne II sold Melksham Court, Stinchcombe, which he had inherited through marriage with the de Mylkesham family, to Sir Walter de la Pole in 1413. His successor, John (owner 1441-1462), was a man of substance, farming the alnage (as an inspector of cloth) for Gloucestershire with Thomas Tanner of Dursley, and defeating the Berkeleys in a suit over property in Cam.

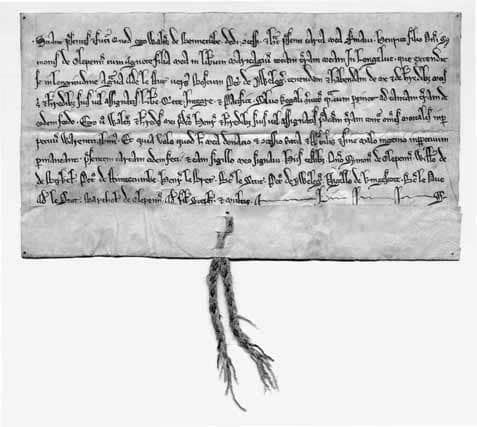

His granddaughter Margery was his heiress and the last of the medieval de Olepennes. Her guardian, Richard Basset of Uley, and her grandmother, Jane, squabbled over the inheritance and had recourse to litigation, Jane pleading her case before the Lord Chancellor, George Neville. A resulting award of 1464 survives in the manor, including a provision for Richard to repair the mill, while Jane was to pay 13s. 4d. towards the cost. The manor house retains fabric from the medieval house of the de Olepennes, identifiably a timber beam dated by dendrochronology to 1294, reused in later rebuilding by the Daunt family.

Daunt family (1462-1815)

Margery de Olepenne married John Daunt, a member of a merchant family established in Wotton-under-Edge since the time of Edward II. Earlier in the century, Nicholas Daunt had married Alice, daughter of Sir William de Tracy, ancestor of the lords Sudeley of Toddington. John’s father, also John, born about 1420, was a Lancastrian, a lawyer at Barnard’s Inn in Holborn in 1446, and elected to the Parliament of 1449-50 for the borough of Wotton Bassett, by which time he had perhaps entered the service of the Crown.

He married Anne, daughter of Sir Robert Stawell, ancestor of the lords Stawell of Somerton. In 1451 he was appointed Keeper of the Royal Park at Mere in Wiltshire, and the following year he was promoted from King’s Sergeant and Groom to the position of Yeoman of the Crown, with a salary of sixpence a day from the issues of Wiltshire. In 1462, in the worst days after Towton, a commission was issued for the arrest of Daunt and others, including the vicar of Mere, “evil-disposed persons, and adherents to Henry VI”.

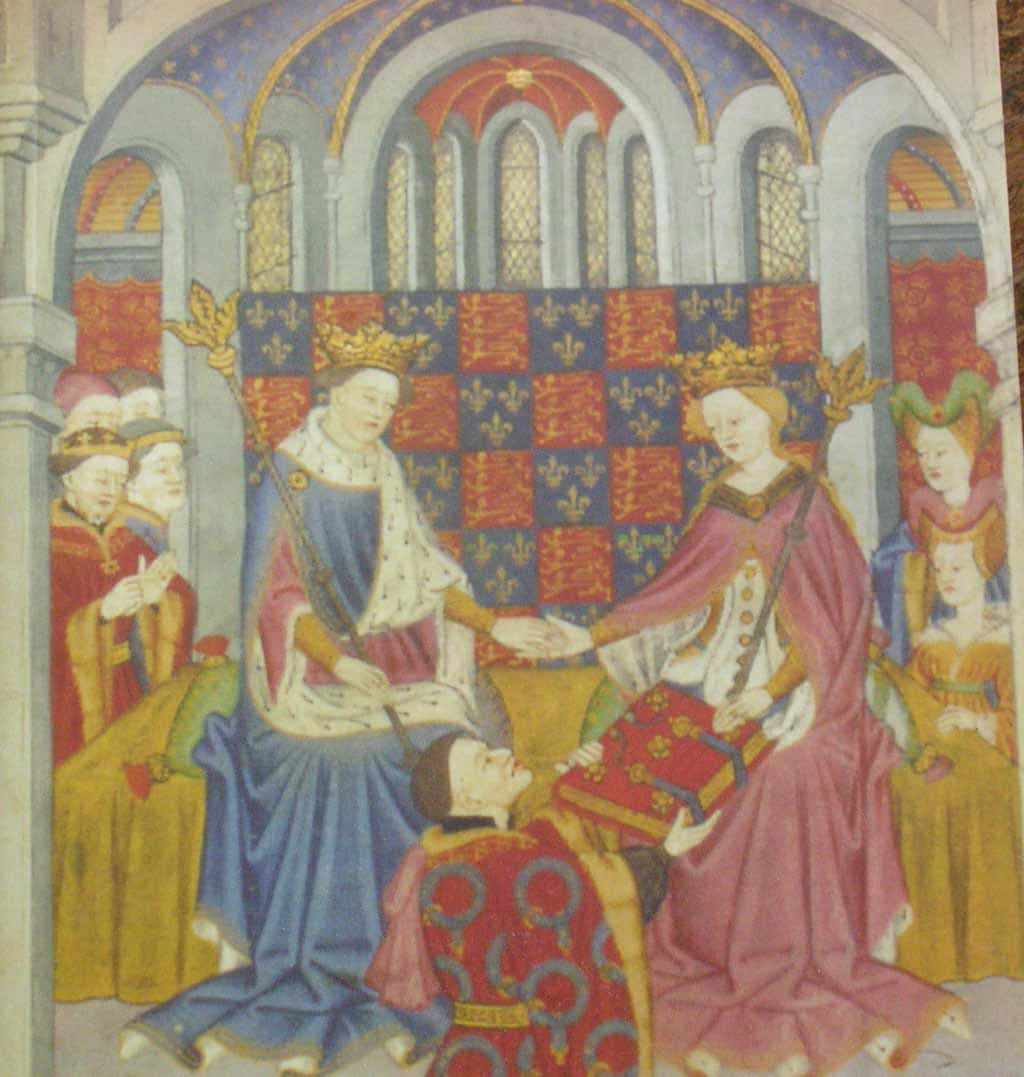

Queen Margaret of Anjou, 1471

In April 1471, the outside world for once brushes against Owlpen. Edward, Prince of Wales, the Lancastrian heir, wrote from Weymouth to John Daunt the elder, asking him to raise “fellowship” and money from Mere and Purton for the Lancastrian campaign:

att our landinge wee have knowledge that Edward Earle of March the Kings greate rebell our Enemy approcheth him in Armes towards the Kinges highnes whiche Edward wee purpose with Gods grace to encounter in all haste possible.

The letter, preserved at the manor till the 19th century, is quoted by Samuel Rudder (of Uley) in 1779.

A tradition in the Daunt and Stoughton families records that Margaret of Anjou, the ardent queen of Henry VI, spent the night of May 2 1471, en route to the fateful battle of Tewkesbury, here. John the younger was doubtless as loyal a Lancastrian as his father, and would have been proud to welcome the royal guest to his manor at Owlpen. Queen Margaret is said to walk in the Great Chamber, a “grey lady” wearing a fur-trimmed gown and wimple — a quiet and apparently benevolent ghost (and one of at least three ghosts recorded in the house).

Sixteenth Century

John and Margery Daunt were richer than the de Olepennes had ever been. It is to their son, Christopher (owner 1522-1542) that we can attribute the building of the centre and east ranges of the existing manor house. The hall dates from 1522 to 1541, with rebuilding of the roof by his grandson, Henry, in 1584-6. The east range is dated 1539.

The alliance of the families is marked by the mid-sixteenth-century heraldic wallpainting showing the arms of Daunt quartering de Olepenne on the north wall of the Hall and, in stone outside, over the hood-mould of the first floor window.

Christopher married a Basset of Uley; his son Thomas Daunt I, more advantageously, married Alice, daughter of William Throckmorton of Tortworth.

The fortunes of the Throckmortons, also Lancastrians and a cadet branch of those seated at Coughton Court, Warwickshire (now owned by the National Trust), were rising, with a succession of knighthoods, the patronage at Court of the earl of Leicester and a baronetcy by 1611. Thomas I entailed the Owlpen and Gloucestershire estates (some 945 acres in total at this time) on his male heirs, which was the unknowing cause of a disastrous family feud in the next generation.

Thomas I and Alice left five sons. Thomas II and William, their second and third sons, settled in Ireland as planters in Munster. Thomas II acquired large estates in County Cork, at Tracton Abbey and, in 1595, at Gortigrenane; the latter comprised (by 1638) “one castle, 100 messuages, 200 cottages, 200 tofts, 200 gardens, 4 mills and 1,000 acres of land”. He was uprooted by the Munster rebellion in 1598 and met with constant difficulties, but was ultimately to consolidate his Irish estates with success.

The fourth son, Giles, of Newark Park, Ozleworth (now also owned by the National Trust), was a keen hunter (and notorious poacher), described by the historian of the Berkeleys, John Smyth, in 1608 as one of “nine men of metal, and good wood-men (I mean old notorious deer-stalkers) armed with nets and dogs” who raided the Berkeley woods and whose detection became a cause célèbre. He told Smyth of himself and George Huntley of Boxwell, that “their slaughter of foxes in Ozleworth have byn 231 in one yeare”. He died in Ireland in 1622, having taken over his pack of hounds.

Meanwhile Henry, the eldest son of Thomas I and Alice, had inherited the Owlpen estate, and completed alterations to the roof and internal arrangements in 1584-6. His mother Alice died in 1599, her epitaph stating: “viginti sex annos vera vidua vixit” [26 years she lived a true widow]. Henry died in 1590, leaving a son Giles to succeed him, and a daughter Frances. But Giles died in 1596 without issue, and Frances was now married to John Bridgeman, an ambitious young barrister of little personal charm.

Bridgeman claimed possession of the estate in right of his wife against her uncle Thomas II, and occupied the house as next-of-kin. Bridgeman’s claim was supported by the influential Sir Thomas Throckmorton, described (by contemporary historian John Smyth) as a “powerfull and plottinge gent … who both made the maryage, and abetted the title”.

Seventeenth Century

The ousted Thomas II returned from Ireland to defend his inheritance, pursuing his claim on the grounds that the estate was entailed to heirs male, to the Star Chamber. It took him twelve years to secure a favourable verdict, making discovery of “plots and practices”. But Bridgeman had secured the manor of Nympsfield and in 1628 purchased Prinknash Park, near Gloucester, when he was appointed Recorder of the city. There was a magnificent fireplace at Prinknash until the 1920s bearing the Daunt/de Olepenne coat of arms, now in an American museum. Bridgeman was later knighted and became Chief Justice of Chester. He is now preserved in marble effigy beside Alice in Ludlow Church, Shropshire. He was a harsh judge and Ralph Gibbon, a local Salopian, composed a scornful pasquinade:

Here lies Sir John Bridgeman clad in his clay;God said to the devil, Sirrah, take him away.

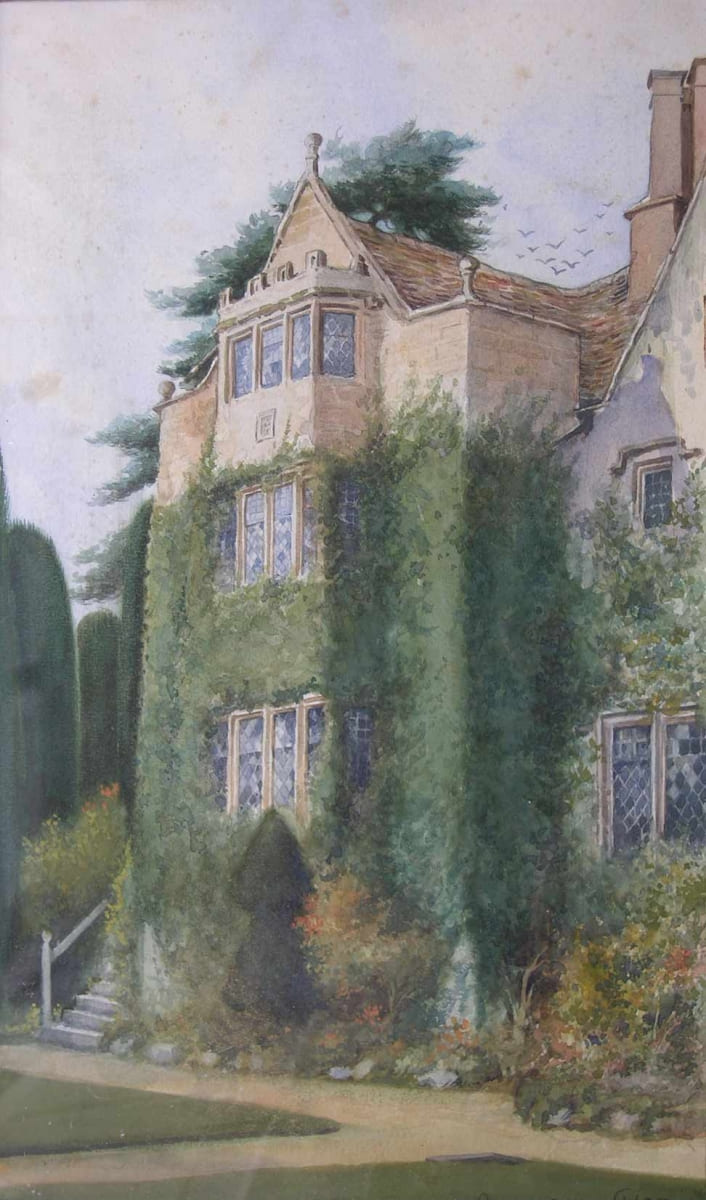

Thomas II had to pay compensation, but it was obviously not crippling: perhaps revenues were beginning to come in from Ireland. At any rate, in 1616 he rebuilt Owlpen’s old solar wing to the west, adding a new storied bay window in ashlar with a datestone and his initials. There was some re-arrangement of the internal accommodation, hearths and chimneys, details and dressings to the gables — with their distinctive owl finials — and fenestration; he probably incorporated the old outhouses in a new kitchen block. His work represents the last major change to the fabric of the manor, so that its appearance today remains much as he left it, having grown by accretions over the century or more to 1616.

When Thomas II died, on August 20 1621, he could look back on much solid achievement. The Daunts were established as landowners in two countries and, though the early death of his Oxford-educated eldest son, Achilles (the first of the family to use that name), was a sorrow, he had other male heirs. His next son Thomas III (owner 1621 to 1669) inherited Owlpen and Gortigrenane. The other Irish estate, Tracton Abbey, went to the line of Thomas I’s third son, William Daunt, and from him a clan of Daunts, carrying the name Achilles or William, colonized the broad southern strip of Cork from Youghal to the Kerry border.

The Daunt principal landed interests, like many of their marriages, were now firmly in Ireland; there, according to John Smyth in 1639, they chiefly resided, so that Owlpen became a mainland base, a secondary estate which an elder son would administer, while the paterfamilias reigned in Ireland. There they joined the ranks of the Anglo-Irish ‘Ascendancy’ and the family by now had some pretensions to gentility: Thomas III was fined in 1630 for not taking up the order of knighthood. Surviving lists of books, in a Catalogus librorum of 1639, in Greek and Hebrew as well as Latin, French and Italian, indicate men of learning.

The seventeenth-century Daunts begin to emerge as personalities, coming alive through a Civil War correspondence for the years 1646 and 1650 preserved between Thomas III in Ireland (where he was High Sheriff of county Cork in 1645) and his eldest son, Thomas IV (1619-1653) at Owlpen. Thomas IV is revealed as an ardent Parliamentarian, jubilant at Fairfax’s successes against the “Cabbs”, and confident that “if God send peace, all will doe well, for the Impartiall Judgement of parliament will confirme right to all.” He writes blow by blow commentaries, mostly culled from his “diurnals”, on the progress of the Parliamentary cause.

Interspersed with these are cryptic requests for his father to act in important and confidential business, requiring his presence and money. He asks for “a barrel of pickled Samphier and some scallop shells”, complains that the cattle are poor, that he has not received his share of a legacy and that only half his library has been sent over from Ireland. He is seen lobbying the Gloucestershire Committee, which included, in January 1646, “Mr Carew Rawleigh, sonne to Sir Walter Rawleigh … Sir Gyles Overbury … and Mr Herbert, who wrote the booke of travaile, a gentleman which understands Arabicke and Persian” (and Charles I’s future biographer), all of whom were expected to be friendly to the Daunts. Thomas IV married the daughter of Sir Gabriel Lowe of Newark Park, but he died before his father and never inherited.

Achilles Daunt (1622-1706) inherited in 1669. He was unmarried and took little part in affairs. Their politics did not prosper the Daunts at the Restoration. Achilles was attainted as a rebel and a traitor by James II’s Irish Parliament in 1689. He was in England at the time and so avoided trouble, although the old castle at Gortigrenane seems to have been burnt down at this time. The Protestant streak was strong, but he was too old to profit from supporting William III. Besides, the Owlpen property was no longer such as to make its owner important: the estate had been eclipsed in size by its neighbours, the house was inconvenient.

Eighteenth Century

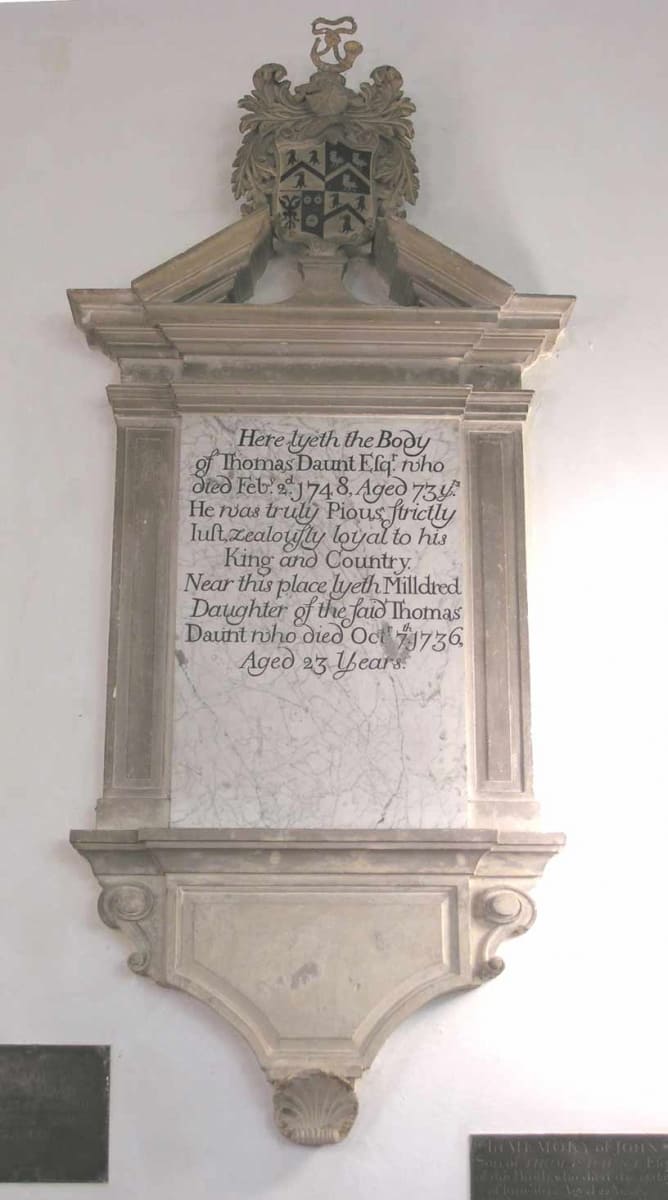

After Achilles died in 1706, the house was hardly occupied for fourteen years. Then, in 1719, Thomas IV (1676-1748/9), Achilles’ nephew and heir, came over from Ireland after his aunt’s death to collect the Lady Day rents, and with intent to build. We see his work as the final building phase, classicizing and symmetricizing details of the old house, making small improvements to its comforts, installing five sash windows and the bolection-moulded fireplaces, panelling the Georgian rooms, raising ceilings, reordering the gardens with their yews and terraces, the gate piers and a palisade, rebuilding the grist mill, the great barn and, finally, the church. All the expenditure is carefully recorded in his surviving account books. Externally his funds allowed him only to reface the façade of the east wing; internally it was a remodelling rather than a reconstruction.

His recorded works about the estate continue actively to 1739; he died ten years later, having raised what was to prove the last family (of seven children) in the house until recent times. His monument in Owlpen Church describes him as “truly pious, strictly just, and zealously loyal to King and Country”.

Two bachelors, Thomas V (1701-1777) and his younger brother Kingscote Daunt (1723-1758), set up house together after their father’s death. Kingscote was a contemporary at Pembroke College, Oxford, of the lawyer Sir William Blackstone and of others whom he proudly lists among those with whom he was on terms of friendship. He officiated as curate of Owlpen (and Wickwar), while his letters show him taking the Bath waters for his ill health and searching for a better living through connections at Oxford and in Ireland.

The estate then passed to Thomas VI (1755-1803) who had already inherited Gortigrenane from his father Achilles, Thomas VI’s twin brother. The house had entered its long period of neglect. He took little interest in Gloucestershire. A surviving notice shows that the last Daunts were contemplating selling the estate with 355 acres:

the estate in hand for living & for farm rent…besides the Mannor House out houses & gardens, a grist mill, some cottages, about 200 akers of well grown wood, situated in a most healthie countrey…any purchaser that will be informed in particulars, himself, his letter or messenger will be kindlie received at Owlpen…by Tho. Daunt.

He kept a carriage and a chaise at Owlpen, which he used as a convenient base for visits to Bath. His accounts from Bath tailors and hairdressers show him as fastidious, buying a “fashionable stripe scarlet Waistcoat”, bows for his boots and shoes, “pound powder and rolers” for his hair, materials in cassimere, marseil[les], shalloon and flannel; and a pair of sidelock pistols from John Richards in the Strand.

Thomas VII was believed locally to have been a magician. After his death, the sealed room in which his books and papers had been kept for many years, was said to be haunted. They were thought so dangerous that parson Cornwall was sent for to destroy them and “as they were burning, birds flew out of them”.

He was to be the last of the Daunts for, on his death in 1803, the male line again failed as it had done 300 years before. By 1807, T.D. Fosbrooke was describing the house as half dilapidated and overrun with ivy.

Stoughton family (1815-1925)

Nineteenth Century: A Sleeping Beauty

Thomas’s daughter Mary inherited as a child of 13. In 1815, she married Thomas Anthony Stoughton (1790-1862), a Kerry landowner who had industrial interests, notably in Monmouthshire coal through his mother, Jane. She was born a Lewis of St Pierre, and Penhow Castle, Chepstow, and was widow of John Hanbury, member of Parliament for Pontypool. Stoughton’s father had managed their estates, but his Hanbury stepsons fell out with him, describing him as “an indigent Irishman” and suing him at Chancery for profiting dishonestly from their mother’s dower and salting away their inheritance.

The manor was by now too small, old fashioned and uncomfortable for the patrician life they intended to live and was soon abandoned for a ‘better’ site at the other end of the estate, a mile away, high on the open Cotswold plateau. There they built a grand and splendid late Georgian mansion, in Italianate style, called Owlpen House, latterly Owlpen Park, allegedly on the model of Arthur’s Club, Stoughton’s London Club.

The architect was Sidney Sanders Teulon (who worked nearby at Uley, Tortworth and Bagpath). Stoughton was well connected: his half brother was Charles Hanbury-Tracy, first baron Sudeley of Toddington and an amateur architect who was chairman of the Committee which chose the Pugin and Barry design for the New Palace of Westminster. Stoughton was an extravagant builder of impressive mansions on his estates: he extended his house at Ballyhorgan, Kerry, in 1812; the Daunt house at Gortigrenane, Cork, was rebuilt as a plain classical block in 1817. The architect was probably Abraham Hargrave Sr.

Owlpen House was completed about 1848, a house of seven bays, with a curious four-story belvedere and extensive conservatories. Today only the lodges, stables and gasworks remain.

It was inherited, after Mary Stoughton’s death in 1867, by her son, another Thomas Anthony Stoughton (1818-1885) and his wife Rose (1840-1924). Rose married again in 1889, after Thomas Anthony died, Colonel H.W. Trent, who added the Stoughton name to his own. Largely to Stoughton family patronage we owe the church above the manor, heavily Victorianized in two phases; in 1828/9, when the nave was rebuilt by Samuel Manning, and 1874, when the chancel was added by Piers St Aubyn. It is their family shrine, with brasses and monuments to the successive generations of Daunts and Stoughtons.

But in other respects the nineteenth century was disastrous for the manor and the parish. The Stroudwater woollen cloth industry, for centuries the mainspring of the local economy, was under check after the Napoleonic Wars, and after a period of expansion with the new steam technology, it could not compete with the north. There were riots and panic and mass emigration from Uley and Owlpen in the 1830s.

Owlpen was badly hit by the failure of Edward Sheppard’s cloth mill in Uley, which employed “nearly all the families at Owlpen”, in 1837. Parson Cornwall at the time described in his (published) diaries how “the improvident weavers were left, almost to a man, utterly desolate. I was obliged to engage to pay the bakers, or whole families would have starved.”

The population of Owlpen declined almost overnight from 255 in 1831 to 94 by 1841, still more than the estate alone could employ. In 1838 it is recorded that 85% of the population of the parish were officially paupers. Parishioners emigrated from Uley and Owlpen to America, Canada (in 1835), Australia (Owlpen House in the Hunter Valley is dated 1837) and New Zealand. The cottages were abandoned (we are told there were 200 empty houses in Uley). The raison d’être of the manor had gone, and the house stood shuttered, a couple named Henry and Hester Grimes occupying a few dilapidated back rooms in the east wing as housekeeper and gardener.

Foremost among their visitors was the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, describing the housekeeper as “the quaintest old body (I bet) you ever saw”, and her husband, who had charge of the garden, as keeping “the old hanging gardens of the 16th or 17th century tidy & sweet & splendid, out of pure love for them.” In August 1894, Swinburne was staying in “one of the most delightful corners of England” with his mother and sisters. He immediately wrote enthusiastically to his friend, the artist-designer William Morris (1834-96), in praise of the ruinous little old manor–house as “a paradise incomparable on earth… Only a poet could describe it—& his name is decidedly not Yours affectionately, A. C. Swinburne.”

There is no record that William Morris ever followed up Swinburne’s recommendation to visit Owlpen, but his inspiration was to be, quite unwittingly, influential on the manner and timing of its rescue.

Thomas Anthony Stoughton II’s widow, Rose, now Trent-Stoughton, had some plans to modernise the ‘Old Manor’ as it came to be called as a more convenient house for herself and her heirs. She commissioned the architect, Randoll Blacking (he did some work at Gloucester Cathedral), to survey the manor and draw up plans in 1921. But in Ireland times were hard. The Daunt estates at Gortigrenane had been sold in the 1880s. The Stoughton lands in Kerry had been sold to the tenants in 1905 and then the Big House, which had been kept on, was abandoned in 1917/18, to be destroyed in the Troubles in 1920/21. Rose Trent-Stoughton died childless in June 1924 and her heir was her nephew, William Anthony Stoughton, an ageing bachelor who gave his address on the first sale conveyance ever signed for the estate as “Arthur’s Club, St James’s”.

Norman Jewson (1925-6)

Cotswold Arts and Crafts

Such was the condition — shuttered and forsaken, yet picturesque in its timelessness — of the manor house when Norman Jewson (1884-1975) first stumbled across it on one of his bicycle excursions from Sapperton before the First World War.

Ernest Gimson (1864-1919) was in the forefront of those carrying on the ideals of Morris into a younger generation and became the leader in the revival of Cotswold Arts and Crafts, moving to the Cotswolds in 1893. He lived for a time (from 1894 to 1901) at Pinbury Park, setting up workshops and showrooms for his furniture at Daneway, another sister house, both on the Cirencester Estate at Sapperton, under the patronage of the Bathurst family.

Norman Jewson was in turn inspired by Gimson and his ideals of ‘fitness’, proven craftsmanship and integrity of design, sensitive repair and honesty to materials. He had been taken on as an “improver” by him, when a newly qualified architect in 1907. Norman Jewson soon settled — and married — in Sapperton also. He describes his encounter with Owlpen:

Another excursion was … to Owlpen, a very beautiful and romantically situated old house, which had been deserted by its owners for a new mansion about a mile away a century before. The house was rapidly falling into complete decay, but a caretaker lived in a kitchen wing and would shew some of the rooms to visitors, including one the walls of which were hung with painted canvas, of the kind Falstaff recommended to Mistress Quickly.

The terraced gardens with a yew parlour and groups of neat, clipped yews remained just as they were in the time of Queen Anne, a gardener being kept to look after them. There was also a large barn containing a cider mill and a massive oak cider press, as well as the old mill of the manor, which had been kept in tolerable repair, as the mill wheel was being used to pump water up to the modern house.

In spite of the dilapidation of the house, which was so far advanced that one of the main roof trusses had given way, the great stone bay window had become almost detached from the wall and huge roots of ivy had grown right across some of the floors, it seemed to me that such an exceptionally beautiful and interesting old house might still be saved.

However, the owner at that time did not wish either to sell it or to repair it herself. Some years later, when the old lady who owned it died, the new owner put the property up for auction, so I was able to buy the old manor house, with [nine] acres of garden and woodland, and put it in repair, though I could not afford to live in it myself.

Owlpen, somnolent and under a spell of enchantment, represented for Jewson all that was vital and enduring in the English tradition, “a noble inheritance”, as he wrote in A Little Book of Architecture (1940); like Kelmscott itself and Daneway, “symbols of the accumulated experience of the past”.

Norman Jewson finally acquired Owlpen and its old garden and outbuildings for £3,200 in July 1925, when the Owlpen estate, including the ‘Old Manor’, its Victorian usurper, Owlpen House, and a number of outlying farms and cottages, in total some 720 acres, was sold in lots.

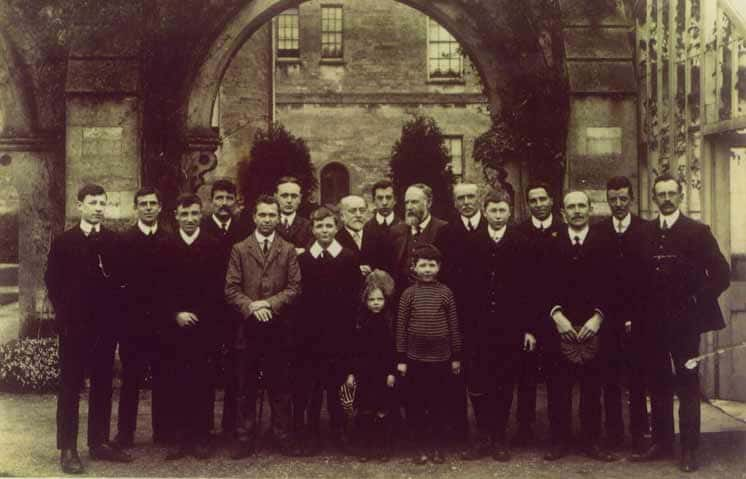

Jewson continued the work of recording and surveying begun by Francis Comstock, and took photographs and watercolour sketches, many of which survive at Owlpen. He engaged a team of craftsmen, employing them as direct labour, photographed at the steps of the garden. Many of them were from the Bisley area and had trained under Ernest Gimson or Detmar Blow, another Arts and Crafts architect who practiced locally. He sought out the sources of traditional materials – timber (he said) from the Uley sawmill; Cotswold freestone, rubble and roofing tiles; ox hair and lime. The frail old house was sensitively and honestly repaired over the next year so that it should assume as near as possible its original beauty.

Jewson was a dedicated member of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings founded by William Morris. He worked under William Weir, one of the most skilful exponents of its philosophy of repair, not restoration. He took great care to preserve the textures of the old manor, all that was resonant and subtle in its fabric, employing the local traditional crafts and skills: lime-based techniques, then in survival as much as revival, and the conservative practice advocated by the Society of “repair by building” and tile repair (e.g., to the hood-moulds).

He used hand-made nails, clouts and spikes (he was proud of these on his own door). The wrought ironwork — forged ‘arrow-head’ and cockspur hinges and Norfolk latches, rat-tail casement stays and bow fasteners, as well as a brass firescreen, grille (to the cellar) and sconces — was made by Alfred Bucknell, at Water Lane, with the help of Fred Baldwin. He retained the Georgian layer of architectural development, sash windows and panelling, which many architects restoring early houses in the 1920s might have suppressed through some misguided purism.

He himself contributed modelled plasterwork, vivid animals and owls, although many of those examples now at Owlpen were cast under his supervision fifty years later, from his own moulds;he enjoyed touching up the sixteenth-century wall-paintings with the enthusiasm of an amateur; he designed cast leadwork for scalloped spouts and the rainwater heads, with more owls and the date. He designed simple furniture and fittings; cupboards, a bookcase and an elm kitchen dresser, apparently made by Peter van der Waals of Chalford.

Much of this work was removed in the 1960s (as was all the original broad glazing) and various projected designs were never carried out: sketches for an internal porch and an owl newel finial survive (although he did bequeath his woodcarving chisels, as much as to say, “Go, and do likewise…”).

The craftsmen were supervised to the last detail of feature and flourish in which he delighted: the traditional pargework of the Tetbury area in a scalloped design made by the plasterer’s hawk to the window jamb surrounds; the diapered patterns of nailheads on the battens of the boarded doors; the laying of a floor as Gimson had taught with the butt ends reversed, so that the boards taper with the bole of the tree, head to tail, a classic example of economy, beauty and use coming together; the swept valleys of the roofs, with proper galetting; graded stone ‘slats’ with their quaint local names, like bachelors and long nines, cocks, wivots and cussoms; the traditional canted chimney tops which were something of a mannerism. He removed the ivy which festooned the whole building, limewashed the exterior rendering, which looks harsh in his photographs, and trimmed the yews.

Jewson’s discovery and subsequent purchase and repair of Owlpen was to be possibly his most enduring achievement. When the work was worthily done, he took some pride in having saved the building and given it new life, describing it diffidently in a letter to Nina Griggs in 1944:

I have never been ambitious in the ordinary sense to satisfy myself of wanting to be somebody. I have always been ambitious to satisfy myself (or my own standards). I suppose I got nearest to it at Owlpen than at any other time.

In the process the house was modestly restyled as the Gentleman’s Residence of the inter-war years, with its servants’ hall and capacious domestic offices, a flower room, two bathrooms, its own water-driven electric plant (in the Grist Mill) and a new-fangled patent heating system, ‘The Pipeless British Marvel’, circulating hot air straight into the Hall from a boiler behind.

The house was too large for him to live in himself and, little more than a year after buying it, he again put it on the market, and it was sold (this time for £9,000) — alas, to his personal loss — in November 1926.

Fred Griggs

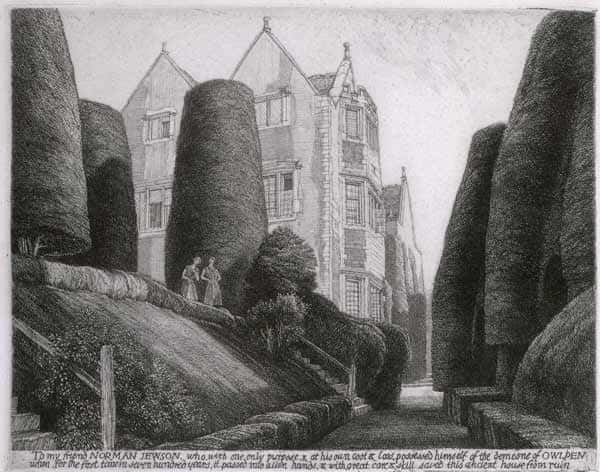

Norman Jewson’s great friend, Fred Griggs (1876-1938) led the revival of etching in a neo-Romantic tradition inspired by the work of Samuel Palmer, Edward Calvert and William Blake, choosing as his subject matter the scenes of an arcadian England of Gothic buildings. He aptly inscribed to him the first state of his etching of Owlpen Manor (1930), a proof of which is in the manor collection:

To my friend NORMAN JEWSON, who, with one only purpose, & at his own cost & loss, possessed himself of the demesne of OWLPEN when, for the first time in seven hundred years, it passed into alien hands, & with great care & skill saved this ancient house from ruin.

The etching is one of Griggs’s most powerful, haunting images, with the gabled manor house overwhelmed, born down upon, by the neatly-trimmed yews to create an airless, claustrophobic sense of tension, relieved a little by the two female figures.

Later David Verey, author of the Buildings of England series guide to Gloucestershire, was to describe how this etching, which became widely known to collectors on both sides of the Atlantic, made of Owlpen an icon, giving it visible and literary form. The house hemmed about by maturing yews became a nostalgic symbol of Englishness for those who had known and loved this part of the West of England and were separated from it during the War years.

Griggs’s celebrated image of Owlpen achieved an iconic status summarizing the values of English civilization which his generation was prepared to defend. “Owlpen in its remote and beautiful valley near the Severn estuary is the epitome of romance”, he wrote. If Owlpen’s story and substance was a romance, Jewson and Griggs appeared its conjurors, awakening its mysteries and making them real for a new generation.

A good deal of work in the Cotswold Arts and Crafts tradition, prompted by Owlpen’s story, survives from this period, including examples now in public collections. A delightful stem pot by Alfred Powell may be seen in the Cheltenham Museum and Art Gallery. A sketch by William Simmonds of the interior of the medieval barn is in the Reading Museum of English Rural Life. Another jewel-like sketch by Jewson’s (and Griggs’s) friend Russell Alexander, much esteemed by Griggs, was left by Jewson to the manor collection. F.L. Griggs’s follower, Joseph Webb (1908-1962), identified with Owlpen, calling his own studio “Owlpen” and producing a magical little etching of the manor for his own letterhead in the early ‘thirties.

Barbara Bray

Jewson sold to Barbara Crohan; she changed her name to Barbara Bray after her divorce in 1939. She addressed him, when she was selling the house in August 1963, “as magician of this resusitated [sic] dream-place”. Owlpen became once again a country house and family home, over which she presided for a generation, bringing life, comfort and light into the building. Her daughter, Bridget, married the ninth earl of Portsmouth.

Barbara was an unforgettable entertainer, a voluble monologuist, active and jolly, whose hospitality attracted many interesting guests, among them Evelyn Waugh, Peter Scott and Joan Evans (who all lived nearby), and a coterie of literary figures, including her cousin, Clive Bell, and many members of the ‘Bloomsbury group’.

The house was becoming well known in an age before the National Trust and country house visiting concentrated the limelight on a few stately and commercial examples. Between the Wars it was described with enthusiasm in the increasing literature on the English country house: the pioneering volumes of H. Avray Tipping (1929), and the books by the country writer H.J. Massingham, by the literary garden-maker Vita Sackville-West, by the young landscape architect, Geoffrey Jellicoe (1926), who was so impressed by the mysterious, medieval atmosphere of the garden, by the American topographical writer Harold Eberlein, by the artist-writer S.R. Jones and, of course, the growing number of local writers on the Cotswolds.

Barbara Bray had a dozen evacuee children to stay from the poor East End of London during the Second World War. Francis Comstock later related how Queen Margaret of Anjou made one of her apparitions:

One night, in making her customary round, she looked in… to see that the four children were sleeping; she found them all awake and excited; they told her of their visitor, “a lovely lady with long sleeves and dress all trimmed with fur, and with a funny peaked hat that had a long veil hanging down behind”, a description of such a costume as Queen Margaret might have worn, and of which the children must have been completely ignorant.

The painted cloths were now recognised as the rarity they are, and Miss Matley Moore made a complete facsimile of them for the National Monuments Record during the War.

Christopher Hussey, another regular visitor who had first seen Owlpen before it was restored “on a dark autumn afternoon in 1925”, empty and sad behind its dripping barrier of yews in the bowels of the valley, painted a number of sketches of Owlpen; the Country Life articles came out in 1952. He deplored, in jocular tone, the extirpation of the four giant yews in the 1950s, writing one of his charming doggerel verses to Barbara Bray on a Reynolds Stone Christmas card:

For the owl hooting inside the pen

The view outwards is better, I’m sure;

And inquisitive architect men

Have no longer to peer and to pore

For a sight of your welcoming door.

But I who like yews

And picturesque views

Am still sorry to lose

The old introvert Owlpen of yore. –

But I won’t go on being a bore

For though I like yew

I really love you

Even more.

Barbara Bray sold Owlpen “very, very tired, & of course, rather sad” in 1963 to Francis Pagan. She wrote to Jewson: “if I must part, I — you — any friend or wellwisher of the manor, & its perfect neighbours, could not hope for more suitable, & understanding new-comers.” Pagan immediately put in hand essential repairs, with the aid of a grant from the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works, particularly to the outbuildings and roofs; improvements were made to the heating, plumbing and services to make the house more convenient (even in the ’20s, such things had not been Jewson’s strong point).

Elsie Matley Moore was enlisted for the conservation, cleaning and rehanging (1964) of the painted cloths so that they could be conveniently displayed in the Great Chamber, which better suited their character. The room from which the cloths were removed was panelled in deal, matching up with some existing panelling installed by Thomas Daunt IV. The house was regularly opened to the public in 1966 for the first time in the summer months, as it has been intermittently ever since. The first old shrub roses were planted in the gardens.

Owlpen today

Nicholas and Karin Mander

Since 1974 Owlpen has been the home of Sir Nicholas and Lady (Karin) Mander (who is Swedish). Their family of five children have been brought up there, Sarra, Marcus, Benedict, Hugo and Fabian, said to be the first family to have been born and raised in the house since the early eighteenth century.

Over the subsequent years the Manders have been fortunate to reassemble much of the old estate, buying back farmland, woodland and cottages. The cottages and outbuildings — including a number of listed buildings — have been repaired and restored as holiday cottages, serving a new generation of guests from all over the world. The Manders have made their lives here, and the manor has become once again the focus of a farm and busy community.

Norman Jewson befriended the Manders in his last years when he was able to renew his acquaintance with Owlpen after long separation. He would reminisce fondly about his work there, although the answers to many eager questions he simply couldn’t remember: “It was rather a long time ago, you know” [fifty years]. He would talk of the Arts and Crafts in all their forms and of the people he had known, and advise tenderly on new projects of conservation and adaptation. He deplored only the grubbing up of the yews and the grandiloquent Victorian restoration of the little Church behind the manor house: “It’s a pity there isn’t a church like the one at Duntisbourne Rouse, but then you can’t have everything!”

He told how Ernest Barnsley would berate his brother, Sidney’s, workmanship by pushing pennies through the gaps between the back boards of his high-backed settle. When he died he bequeathed the settle, which had belonged to Gimson at Pinbury, to Owlpen, as well as his Barnsley work table, and sketch-books and verses, and the diaries he kept of his Continental travels.

The Mander family, too, has its links with the origins and ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement. The Manders were pioneer industrialists. Thomas Mander, a younger son, moved from the Warwickshire villages in which the family had settled by the thirteenth century to Wolverhampton in 1745.

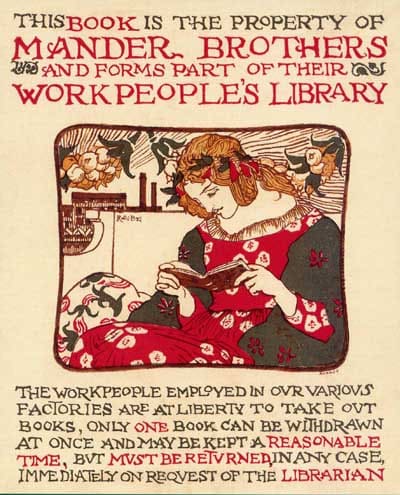

His sons, Benjamin and John, prospered as merchants. They established, in 1773, amongst a variety of enterprises, a japanning and (later) varnish, paint and ink businesses which continued for 250 years, and as Mander Brothers went on to produce the leading brands of the Empire.

The family were (in the eighteenth century) nonconformists and philanthropists, who became involved in many charities and public causes, in county and civic affairs in Staffordshire, in the yeomanry, in the arts, and local and national politics.

Nicholas Mander succeeded to the family baronetcy in 2006. The title was awarded to Charles Tertius Mander for public services over many generations in the Coronation honours of George V, in July 1911.

As patrons of the arts, the family are notable for the two adjoining houses which were built (or rebuilt) for them by Edward Ould in the ‘Old English’ style in the final decades of the nineteenth century.

The Mount, the principal family house, is a grand house in neo-Renaissance style. It is now a hotel with some sixty bedrooms, although many of its contents survive at Owlpen.

Wightwick Manor is in a delicate and self-consciously picturesque ‘Cheshire Tudor’ idiom whose textures owe much to the late-nineteenth-century rehabilitation of houses like Owlpen. It was presented to the National Trust, the first country house to be so presented in the lifetime of its donor, by Sir Geoffrey Mander, Liberal MP for East Wolverhampton, in 1937.

Today it is preserved intact as something of a period piece, much enriched by the outstanding collections of Pre-Raphaelite art and William Morris furnishings, augmented by Sir Geoffrey and his wife, Rosalie, Lady Mander, who became authorities on the circle of William Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites. Norman Jewson commends Lady Mander’s book on Rossetti in a letter to Nina Griggs in 1966, “to my mind, a really good and sympathetic biography.”

Owlpen represents these traditions — of long history, solid building, romantic survival, sensitive repair and adaptation, creative enterprise and public service, hospitality and a little eccentricity — which may still be an inspiration to those who visit today.

For more information about Owlpen and its history, please se our guidebook, available to download here